Is it worth the time?

One of the things I have been thinking about lately is how to further increase my own productivity. Regardless of your career goals, increasing your productivity is only going to help you accomplish more (by definition) and increase your esteem as a professional. Productivity is an interesting concept to me because it is, to a large extent, quantifiable. How many papers did you publish this year? How much funding did you bring in? What kinds of committees did you serve on and what did you accomplish exactly? All of these variables represent some measure of a person’s productivity. Naturally, a lot of effort is spent on determining what the best measures of an individual’s productivity are – and this is a very healthy and necessary practice. For academics and researchers, these measures usually boil down to the quality and quantity of published papers (not always in that order).

So what doesn’t productivity measure? It certainly does not measure how much time you spent on a particular project. If one calculated the total number of hours that went into every Molecular Ecology paper, I would guess that the variance would be large, and the range would be remarkable. As a graduate student you have to learn things like statistics and computer programming – tasks that can take a lot of time. In short, productivity does not measure time and effort (i.e., work), even though these things in turn contribute to productivity.

As an example, I recently attended a campus-sponsored workshop for those pursing academic careers. In one of the sessions, we were presented the results from a campus-wide survey that illustrated that assistant professors typically work 60-70 hours per week. Associate professors, on the other hand, typically work 50-60 hours per week, even though their productivity is equal to or greater than their less-experienced counterparts. This may not be a perfect example, but it does lead to an observation that follows from personal reflection: experience leads to efficiency and efficiency is one key component to productivity. As an early graduate student, it could take me a long time to write a simple script or to perform relatively simple analyses. As I gained experience, I became more efficient: more efficient at managing my time, more efficient at writing scripts, more efficient at writing papers etc. This was an ongoing experience and it certainly did not happen overnight.

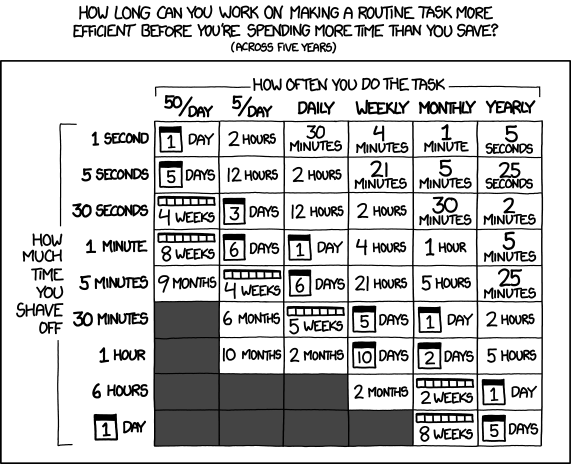

Because efficiency is such a large part of productivity, I think it is important to critically evaluate how you can become more efficient at whatever you do (i.e., whatever you would like to be productive at). As illustrated in the comic above, though, it is most important to become efficient in things that matter (writing, for example) and things that you will do often. I also think it is critical to recognize that you are a unique person: what works for you may not work for everybody else. Advice you read on the internet can be helpful, but it can also be the complete opposite strategy to what works for you. I try to take a scientific approach: I read advice critically (so read this critically!), and I experiment with trial and error. I have found that, for me, checking facebook only once per day really helps with my efficiency. However, I also know incredibly efficient people that check it much more often – for them, a brief but regular monitoring of social media acts as a reset button that allows them to continue to work efficiently.

So what else contributes to productivity? Luck certainly can play a role. Experiments can fail, advisors can be mediocre, grants and papers can receive unfavorable review. These things will hinder your productivity. But luck, or lack thereof, is stochastic. Some people may appear to be lucky (and a smaller portion may actually be so), but in reality these people have simply figured out how to be more productive. It is disconcerting to think about the fact that after all the time and work invested in a project, it may fail. If it fails, you might be tempted to think “well that was unlucky” – and you may very well be right. One key to productivity, however, is determined by what you do next. Do you incorporate reviewer’s comments and resubmit to a different journal as quickly as possible or do you become dispirited and think about pursuing an alternate career? In the sciences, perhaps more than other fields, you need a thick skin, a dogged determination, and true passion for your field of study. Luckily, the first two traits can be acquired with experience.

To summarize this post so far, I have made the arguments that you need to be efficient in order to be productive, and one key to efficiency is simply experience. Surely efficiency and experience are not the only two things that lead to productivity, however. I suppose another thing worth thinking about is how to best increase your efficiency and, more importantly, gain the right type of experience to become a productive person. This responsibility is largely your own, though good advisors and colleagues will steer you in the right direction. You are ultimately (and fortuitously!) in charge of how you spend your time and careful reflection in this area will help you acquire the experiences you need to become a productive person.

The last point I would like to make, which largely goes without saying, is that collaboration will not only increase your productivity, but will greatly enrich your personal, professional, and intellectual experiences. So, collaborate whenever possible!

This post has taken a very general view. It would be great to hear your thoughts below. What has helped with your efficiency? What tips (big or small) have helped you become a more productive molecular ecologist?

Oh, the irony…..